March In The Annex: Damon Campagna, Deborah Peeples and Ponnapa Prakkamakul

In March in the Annex, we see artists Damon Campagna, Deborah Peeples and Ponnapa Prakkamakul expose the human experience through mark-making and collecting. Using printmaking, painting and encaustic, these three artists collect, expose and obscure our surrounding environments.

The show will run through March 31st. Below you can learn more about these three artists and their work.

Damon Campagna

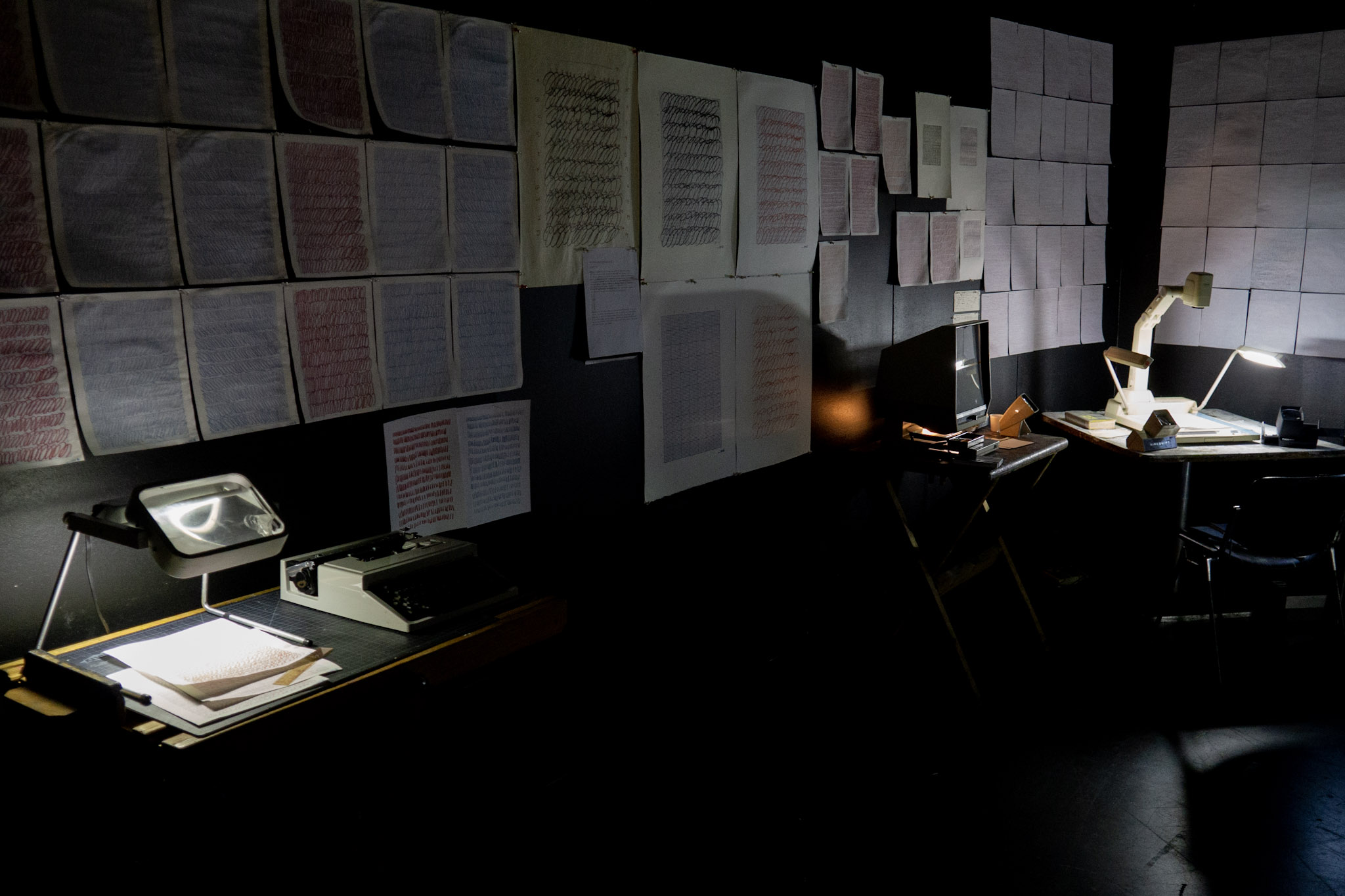

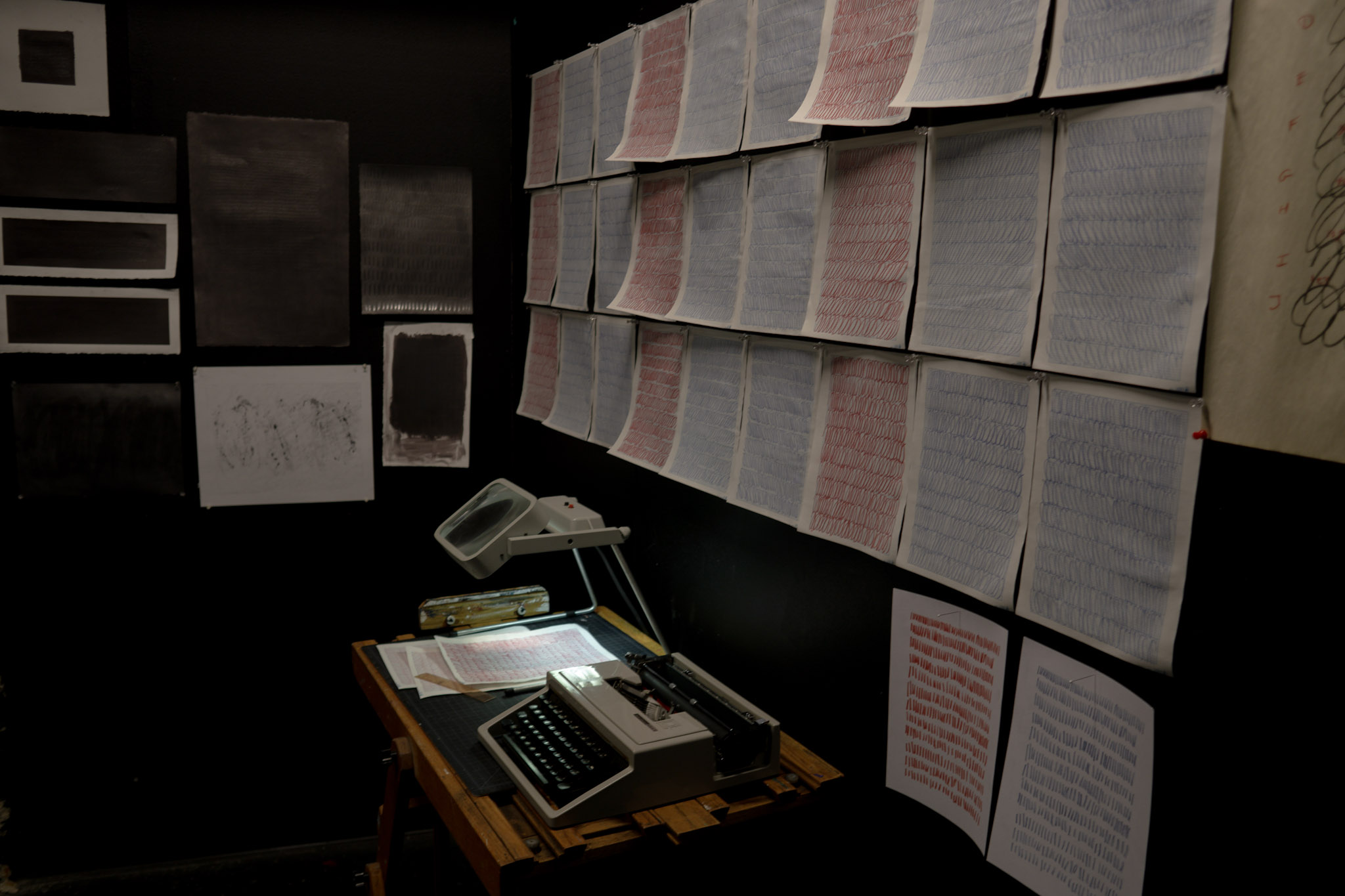

My work is summed up in my Artist’s Statement: If one assumes basic mark making is as unique to the human being as a heartbeat, running gait or sleep pattern, can it be similarly quantified, recorded and studied? Would it enable one to establish any sort of deeper, metaphysical “meaning” behind one’s art, and if so, what would it be? Through drawing, painting and printmaking, I investigate methods in which the most elemental human mark making information, lines and loops, can be cataloged and recorded in an existential attempt to define “self." As the artwork is intimately linked to the process of its documentation, I also ask who would bear the consequences of both obsessively producing and collecting in a pursuit of the potentially unknowable.

When I initially started exploring the idea of the mark as part of the extended self (which is the self, plus the “stuff” that we possess or create that helps define our identity), I soon realized that that the business of analyzing the mark in a literal sense wasn’t all that interesting. After all, tech companies are constantly analyzing artwork in an attempt to catch creativity in a bottle. Christie’s recently held the first auction for an AI-created artwork, produced by an algorithm studying 15,000 portraits. Evidently a large data-set is required to discover the sort of patterns needed to create a $432,500 portrait from scratch.

However, it was much more compelling to think about the person who might be looking at these marks for answers. Someone looking for meaning in their own mark making, searching for patterns that might answer the “big picture” questions in life, like why am I here?

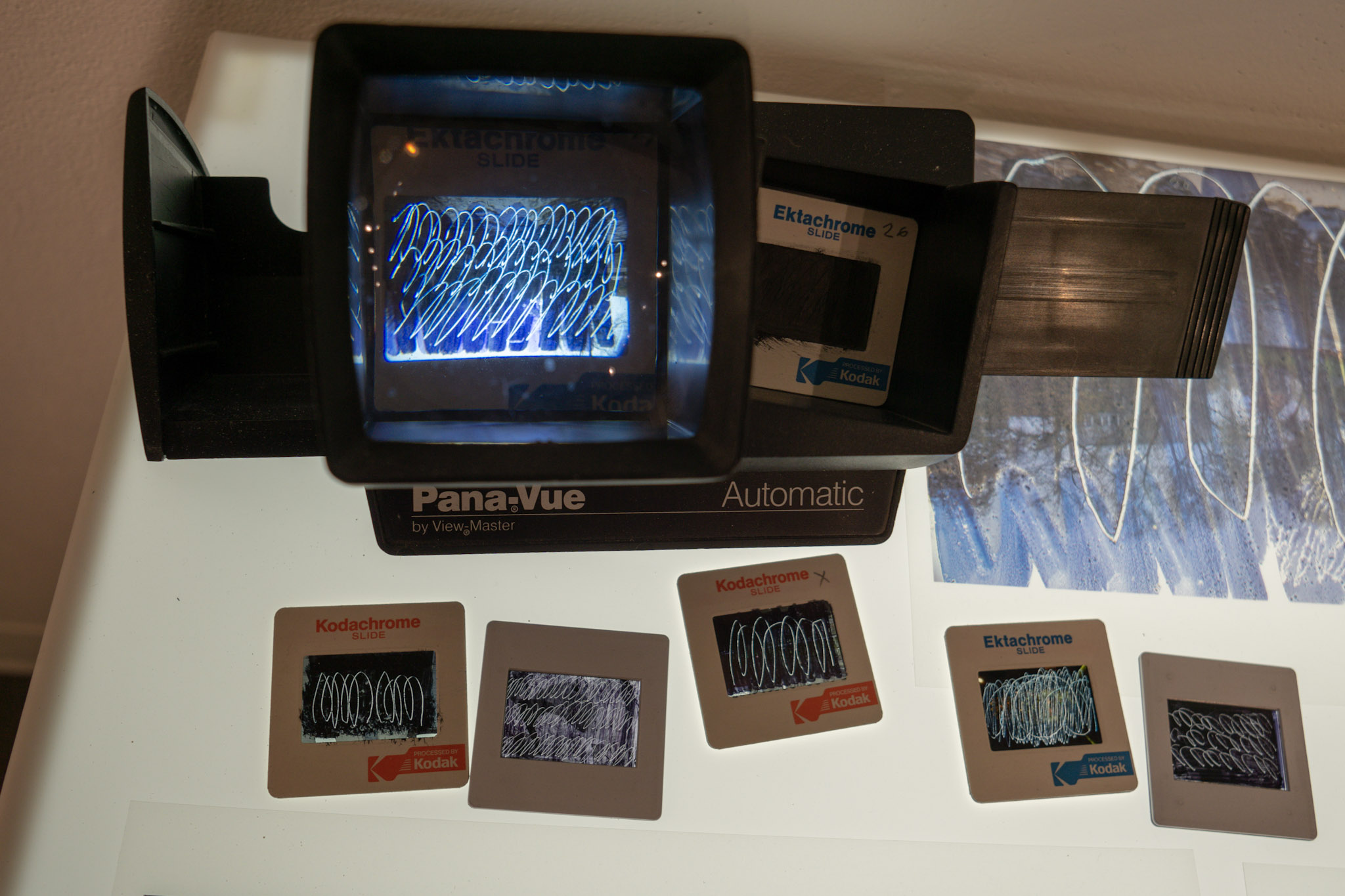

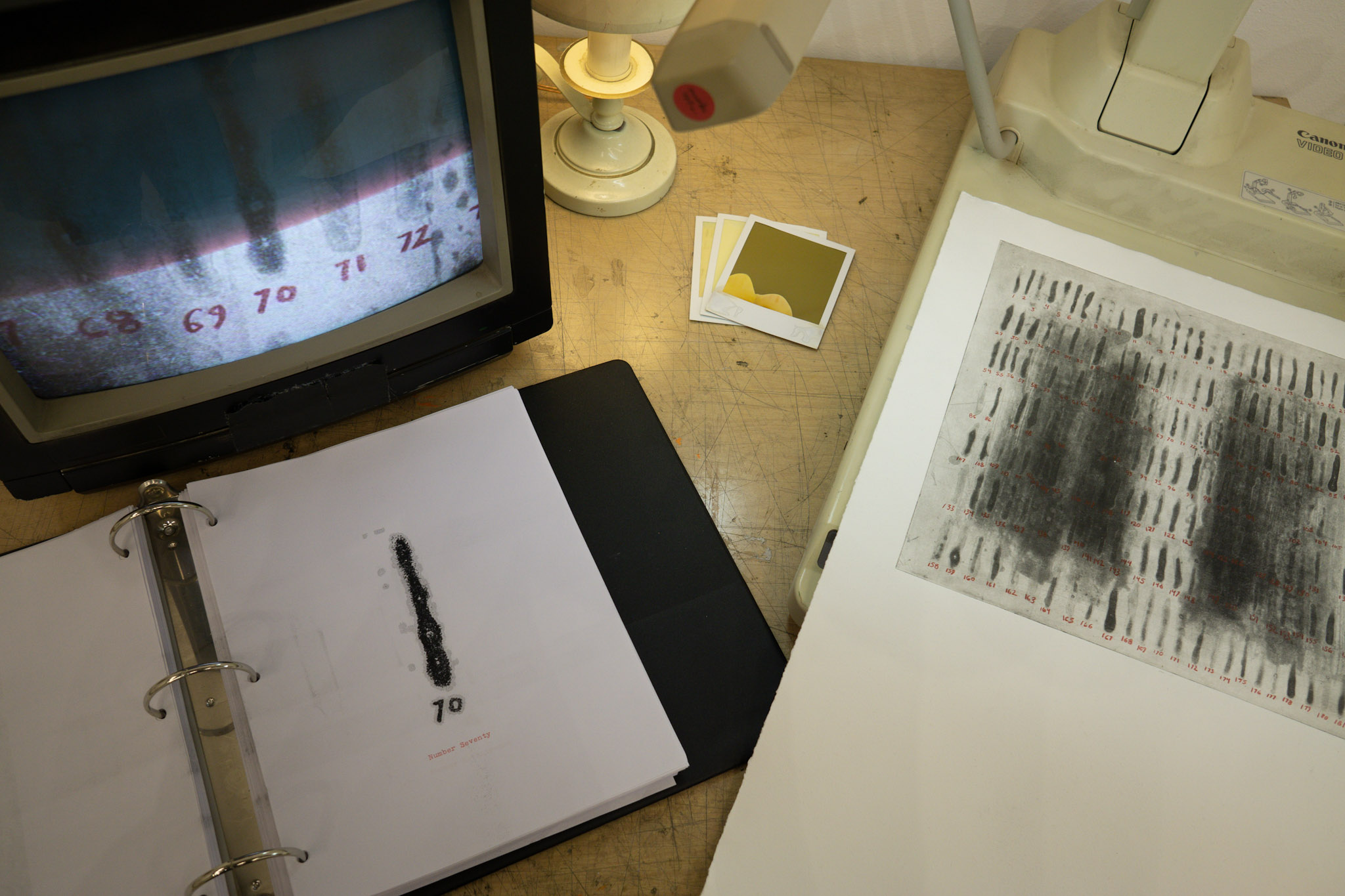

What does that pursuit look like? How would that person define their data-set? Obviously, there would have to be a lot of information – obsessively created, as patterns only emerge with big numbers. I decided there would be a set of rules defining two states, the loop and the line (or mark) and determined procedures to follow to maintain consistency. Also they would create some system for cataloging their collection. From my museum experience, I’ve found that most collectors or small museum owners don’t follow any traditional cataloging system or nomenclature, they often create one based on what they think a professional museum does but built on their own idiosyncrasies and needs. Also, they don’t use special museum collection software for their material – sometimes their catalog just resides in a spiral-bound notebook or 3x5” index cards, and they simply use the equipment around them. They work with what they know.

So, my graduate work is about probing this imaginary metaphysical quest to find meaning in the scrutiny of one’s own work, of indexing these marks and cataloging them. The project opens up a lot of questions. What would prompt someone to do this in the first place? PTSD? Mid-life crisis? And end-of-life review? Mental illness? And what happens to all this stuff? Where does it go? Does the collector inevitably collapse into what Walter Benjamin called “the allegorist,” for whom “objects represent only keywords in a secret dictionary, which will make known their meanings to the initiated -- precisely the allegorist can never have enough of things.” In other words, when does the collection become a hoard, with things produced and heaped with no rhyme or reason known outside that of their creator? So mental illness and hoarding becomes part of the narrative, too.

Deborah Peeples

A central theme of my life has been the ways in which we protect ourselves and present to others. As an adoptee and parent of a transgender child, the superficial structures we cultivate and the exposure of our core vulnerability are central to both my artwork and past work as an activist. I have always explored questions about our intrinsic desire to be seen and valued, and the assumptions we maintain about ourselves and others around how we fit in the world. My work is concerned with preconceptions about what we see, and how this might be altered as we become more sensitized to what lies beneath the surface

My abstract paintings explore space, distance, and perception through the natural translucent materials of beeswax and resin, which allow the creation of atmospheric as well as sculptural surface treatment. My surfaces are carefully smoothed and polished, although trace marks are discernible on close inspection. Below the surface, shapes appear and disappear, losing form or popping to the surface as they journey through sensual pools. The lush color and saturated silhouettes invite you to reflect, take a closer look, and journey more deeply. My process is to alternatively build many layers, overlaid and adjacent, and scrape them back, allowing me to choose how much to expose or obscure. I see this as both method and metaphor for uncovering and connecting with my inner self.

I typically works in series, working though self-imposed problems and limitations. My most recent paintings are part of a larger body called “Desire and Longing,” which explores concepts of discipline, restraint and abandon.

Ponnapa Prakkamakul

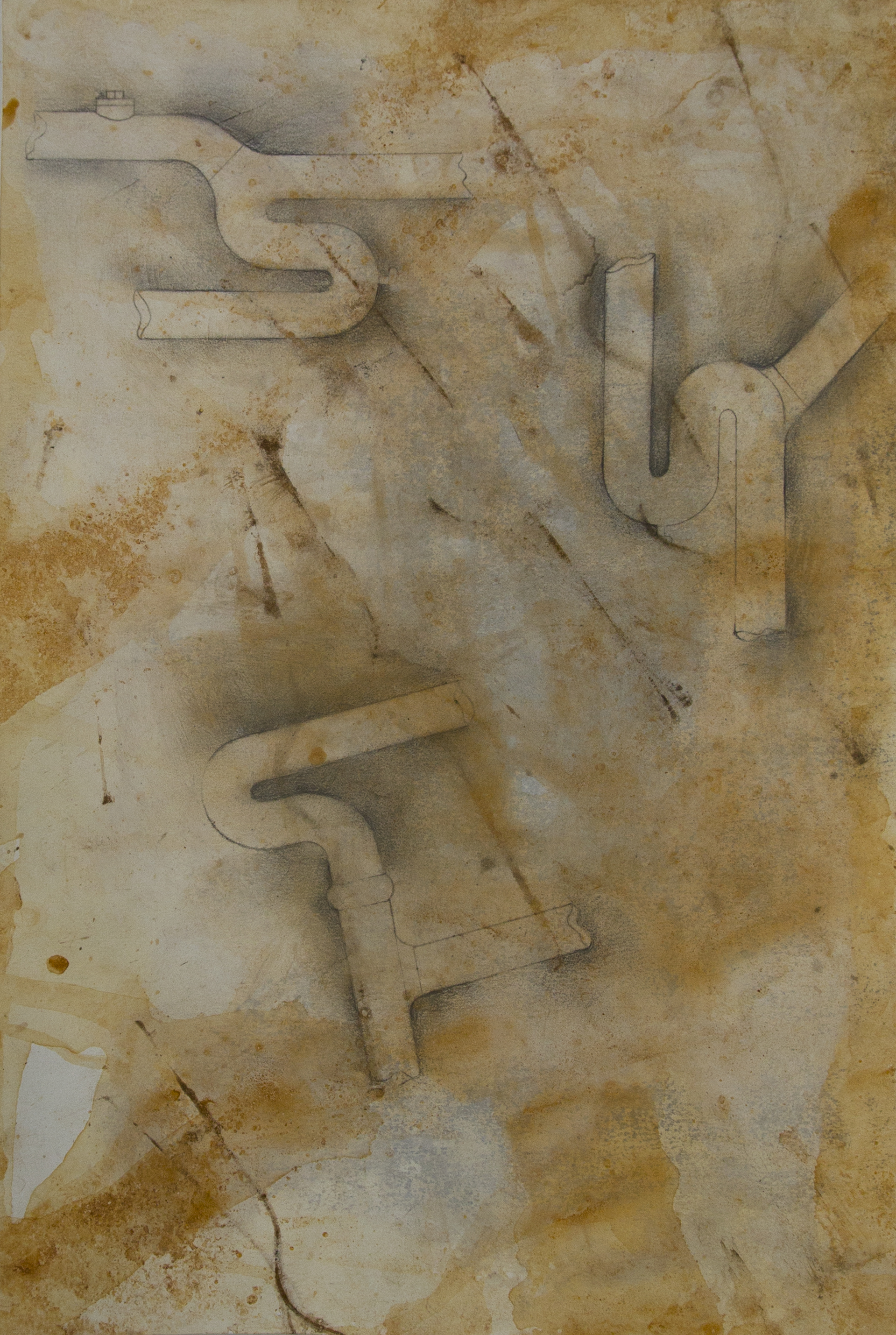

As a painter and a landscape architect, a site is an important part of my work. My work explores the use of the painting process as a tool to experience and understand the surrounding environment. The process begins at the site by using the performative act of searching, studying, and collecting natural painting materials in addition to sketching in situ - establishing a more immersive experience and engagement with the landscape. In a studio, the collected materials are applied on paper as the painting medium. For me, this process not only creates a connection between myself and the site but also allowing me, who relocated to the United States in 2009, to form a deeper connection with places. The manner of soaking Stonehenge paper into the river creates understanding of the profile of the water edge. The tree bark’s print on paper also imprints a memory of that tree in my mind. Through the making of the art, I gradually identify my place in this new ground.

In my current work from 2018 Manoog Family Artist in Residence at the Plumbing Museum, I used the same methodology to explore historical sites with man-made structure and introduce a new drawing medium, rust. Similar to organic materials such as plants and soil particles, rust reacts to different level of oxygen, moisture, and pH creating variety of textures and colors. These variations reflect the conditions of the site bringing the viewers closer connections to the painted scenes.